How Empathy Makes Us Cruel and Irrational

The strange movement to free the Menendez brothers

On 20th August 1989, 21 year-old Lyle Menendez and his 18 year-old brother Erik burst into their parents’ Beverly Hills mansion, and shot them dead. They claimed they’d done it because their parents had sexually abused them. In 1996, after two highly publicized murder trials, the brothers were found guilty and jailed for life.

Now, decades later, interest in the case has surged again. In September, a Netflix show based on the murders became the most watched show on the platform, and the Menendez brothers’ wiki page became the most viewed entry on Wikipedia. Over 400,000 people – mostly women – have now signed a petition to free the brothers, arguing they’re victims whose claims of sexual abuse were not taken seriously in the 1990s. Their demands have been echoed by high profile figures like George Gascón, who, as District Attorney of Los Angeles County, recommended Lyle and Erik be resentenced and released. Next month, the brothers will attend a hearing that could finally see them freed.

The problem is, the brothers are not actually victims. They’re liars and murderers. And the only reason they now have widespread support is that culture and technology have turned empathy into an emotionally transmitted disease that debilitates thought. Put simply, stupidity has gone viral.

The facts of the case are well-established: the brothers initially blamed the murders on the mob, but Erik later confessed to his therapist, Dr. Jerome Oziel, that he and Lyle were responsible. Erik claimed they killed their father, José, because he was domineering, and their mother, Kitty, because she was hopelessly depressed. Neither Lyle nor Erik mentioned sexual abuse to Oziel. Nor did they mention it to their first lawyers, Gerard Chaleff and Robert Shapiro. Their abuse claims only emerged after they met Erik’s second lawyer, Leslie Abramson, several months later.

Abramson had recently helped 17 year-old Arnel Salvatierra avoid a murder conviction for killing his father. She’d done this with a new kind of legal defense; portraying Salvatierra as a victim of abuse by his father. Evidently, she believed this approach could also work for Lyle and Erik.

However, to clear the brothers of murder, it wasn’t enough to make the case they’d been sexually abused, because murder committed in revenge for abuse is still murder. Abramson also had to show the brothers believed they were in imminent danger from their parents, and were acting in self-defense. But this claim was disproven by the clear evidence of premeditation – Lyle and Erik forged the paperwork to purchase two shotguns before the shootings – and the fact that, after their first volley of gunfire, while their mother was writhing in her own blood, the brothers left the home so Lyle could reload before returning to finish her off.

Nevertheless, Abramson, together with Lyle’s lawyer Jill Lansing, decided to build a self-defense case, arguing the brothers had acted after confronting their parents about the sexual abuse, causing their father to threaten them, which in turn caused Lyle and Erik, traumatized by decades of abuse, to panic. This was a tough strategy because not only was there no good evidence the brothers had been in imminent danger, there was also no good evidence they’d been sexually abused.

The abuse claims rested on questionable items like a doctor’s report of an unexplained throat injury Erik got aged 7, declared by expert witnesses as possibly caused by oral rape. Other evidence included an envelope in Kitty’s possession that contained two nude photos of Erik and Lyle as boys. However, the angles of the photos suggest they could’ve been selfies.

There was much better evidence the brothers were greedy. Days after the murders, they embarked on an extravagant spending spree, buying Rolexes, Porsches, and even a buffalo wings business. Further, Erik told Oziel he’d feared his father would disinherit him, and Lyle hired a computer expert to delete what was likely his father’s recently updated will, preserving the original 1981 will, which left everything to Lyle and Erik.

The brothers had already shown they were willing to commit crimes for money. A year before the murders, they were caught committing a string of burglaries in their Calabasas neighborhood, stealing around $100,000 in goods.

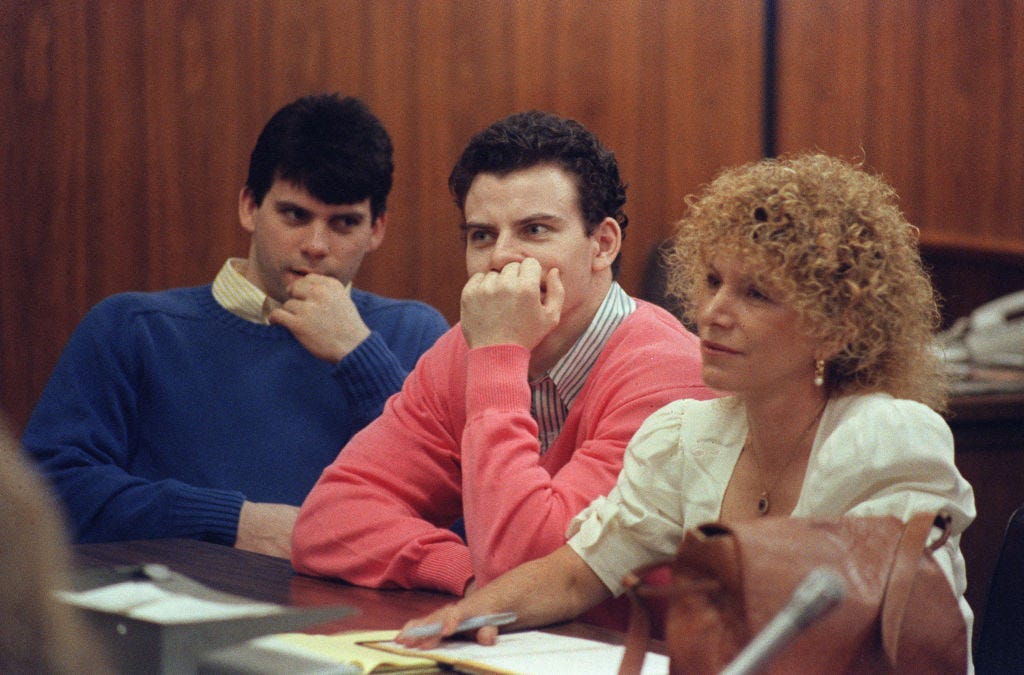

Given that Lyle and Erik didn’t have the facts on their side, their lawyers had to get creative. Abramson and Lansing tried to portray the brothers as sweet and naïve kids. They dressed them in boyish clothes like school-style sweaters. Lansing kept referring to them in court as “the children”, and Abramson would often maternally place her arm round Erik, and pick lint off his sweater. Her behavior was so conspicuous the judge reprimanded her for it.

But the lawyers’ infantilization of their clients wasn’t just restricted to gestures. To sell the brothers as abuse victims who feared for their lives, Abramson and Lansing turned to the wealth of abuse-related pseudoscience in the field of psychology. For instance, they used a vague checklist of sexual abuse symptoms developed by therapist E. Sue Blume, an advocate of the pseudoscientific idea of repressed memories, which in the eighties and nineties led to many people being jailed for sexual abuse they didn’t commit. Abramson and Lansing also received diagnostic advice from Paul Mones, a lawyer with no clinical training. Eight of the things the brothers claimed their father had done to them, such as poking them with pencils during rape, are mentioned in case studies in Mones’ book, When a Child Kills.

The brothers’ aunt Terry Baralt apparently told the journalist Dominick Dunne that Lyle and Erik had read Mones’ book in jail. This was corroborated by a prisoner who shared a cellblock with Lyle for over two years, and told the prosecutors Lyle had read every book he could find on child molestation. It’s therefore likely the brothers had the knowledge to fool psychiatrists into diagnosing them as abuse victims.

Some of Lyle and Erik’s friends and family also came forward to testify for them. The strongest testimony came from the brothers’ cousin Diane Vandermolen, who claimed Lyle told her when he was 8 that he was being abused. But the credibility of her testimony became suspect when it transpired Lyle had repeatedly tried to get friends to lie for him.

Ultimately, the jury was unable to reach a verdict in either Lyle’s and Erik’s cases, so a new trial was held in which both brothers were tried together. Since Abramson and Lansing had failed in the first trial to show that the brothers’ supposed sexual abuse gave them a valid self-defense argument, testimony regarding the abuse allegations was limited by the judge in the second trial. Under these conditions, the jury at the second trial reached a unanimous decision that Lyle and Erik were guilty of murder, and the brothers were jailed for life with no possibility of parole.

In other words, justice – according to contemporary California law – was done. The brothers received the sentence they were due, because even if they had been sexually abused (which they likely were not), they had no case for self-defense. They planned their parents’ murder, killed them while they were watching TV, and then celebrated by lavishly spending their money.

And yet, decades later, millions of people are now treating the brothers as victims.

This isn’t the first time this has happened. In 2015, the Netflix documentary Making a Murderer deceived millions of people that the rapist and killer Steven Avery was an innocent victim of corrupt police. A petition to release Avery was signed by over half a million people – again, mostly women – despite the significant evidence against him.

So why are people, and particularly women, so easily convinced that cold-blooded killers are victims? It can’t simply be a lack of intelligence; while support for the Menendez brothers is currently being led by celebrities not famous for their IQs, such as Kim Kardashian and Rosie O’Donnell, equally gullible campaigns for murderers have in the past been led by respected intellectuals.

In 1977, the Pulitzer prize-winning novelist Norman Mailer was awestruck by the writing ability of the convicted killer Jack Henry Abbott, and, convinced he was reformed, called for his release. The wish was granted, and Abbott used his newfound freedom to stab a waiter to death.

A few years later, Nobel Prize-winning novelists Günter Grass and Elfriede Jelinek, touched by the writings of rapist and murderer Jack Unterweger, petitioned for his freedom, and when he was released he celebrated by raping and murdering nine more women.

The award-winning authors who misplaced their trust in murderers may have been deluded, but they can’t be accused of being particularly stupid. Instead, their delusions were born of a more surprising weakness: empathy, or the tendency to try to feel what others feel.

It was after reading the eloquent words of Abbott and Unterweger, and walking in their supposed shoes, that the novelists began to push for their freedom. And it was after being transported into the apparent shoes of Steven Avery via Making A Murderer that half a million people petitioned for his release.

The Menendez brothers were masters of evoking both empathy and sympathy. Erik was an aspiring actor and Lyle admitted to his biographer Norma Novelli that he practiced how to cry convincingly. The 911 call the brothers made shortly after killing their parents, in which they wailed and wept while lying that they’d innocently stumbled upon their parents’ bodies, shows they were both convincing actors.

Like Abbott and Unterweger, Lyle and Erik were also imaginative storytellers – both had written works of fiction – and they used their skills to embellish their story of abuse with intimate, if sometimes far-fetched, details. For instance, Erik claimed he secretly laced his father’s tea with cinnamon so his semen would taste better (this made no sense, since José would easily have detected such a strong flavor in his tea).

The brothers made heavy use of their acting and storytelling abilities in the first trial, telling vivid tales of abuse while weeping with cinematic gravitas. Both brothers sought to portray Erik as the main victim of abuse and Lyle as his heroic protector. Back then, just as now, their claims proved more persuasive to women than men; Erik’s trial resulted in a hung jury, with all six of the male jurors pressing for a murder conviction, and all six female jurors pressing for a lesser conviction due to accepting the brothers’ claims of abuse.

One reason for this disparity may be that women, like award-winning novelists, tend to be more empathic than the average man. A substantial number of studies have found that in mock sexual abuse trials, female jurors tend to be significantly more empathetic toward the alleged victims, lending greater weight to the expressed emotions and personal testimony of the alleged victims when deciding on the verdict.

Further, research has found that in a Menendez-style mock court trial in which the defendant was charged with killing their allegedly abusive father, female jurors, and jurors who were specifically encouraged to empathize with the defendant, were more likely to believe the defendants’ claims of abuse and consider them innocent of murder.

The same crocodile tears that disproportionately convinced women in Erik’s first trial now also seem to be disproportionately convincing women on social media. Since 2020, footage of the brothers’ emotional courtroom performances has been frequently sliced into snippets, set to heartfelt music, and posted on TikTok, where they soon started going viral, leading to the present craze.

But it’s not just social media that’s to blame. The world is not just technologically different from the 1990s when Lyle and Erik were convicted; it’s also culturally different. And culture has been pivotal in spreading falsehoods about the Menendez case.

To understand how culture has changed, we need to look again at the gender difference in empathy. This difference doesn’t just affect the verdicts of juries. It likely also impacts the entire field of psychology, which in the 20th century was dominated by men, but in the 21st has increasingly become dominated by women. Between 2011 and 2021 the share of registered female psychologists in the US increased from 61% to 69%, and in the UK, women now make up over three-quarters of all registered psychologists. This demographic shift has been accompanied by a shift in the way psychology is conducted, from the old masculine approach of objectifying humans as specimens to be studied with cold and often cruel detachment, to a more feminine, empathic approach that centers the feelings and lived experience of those under examination, even if this conflicts with objective reality.

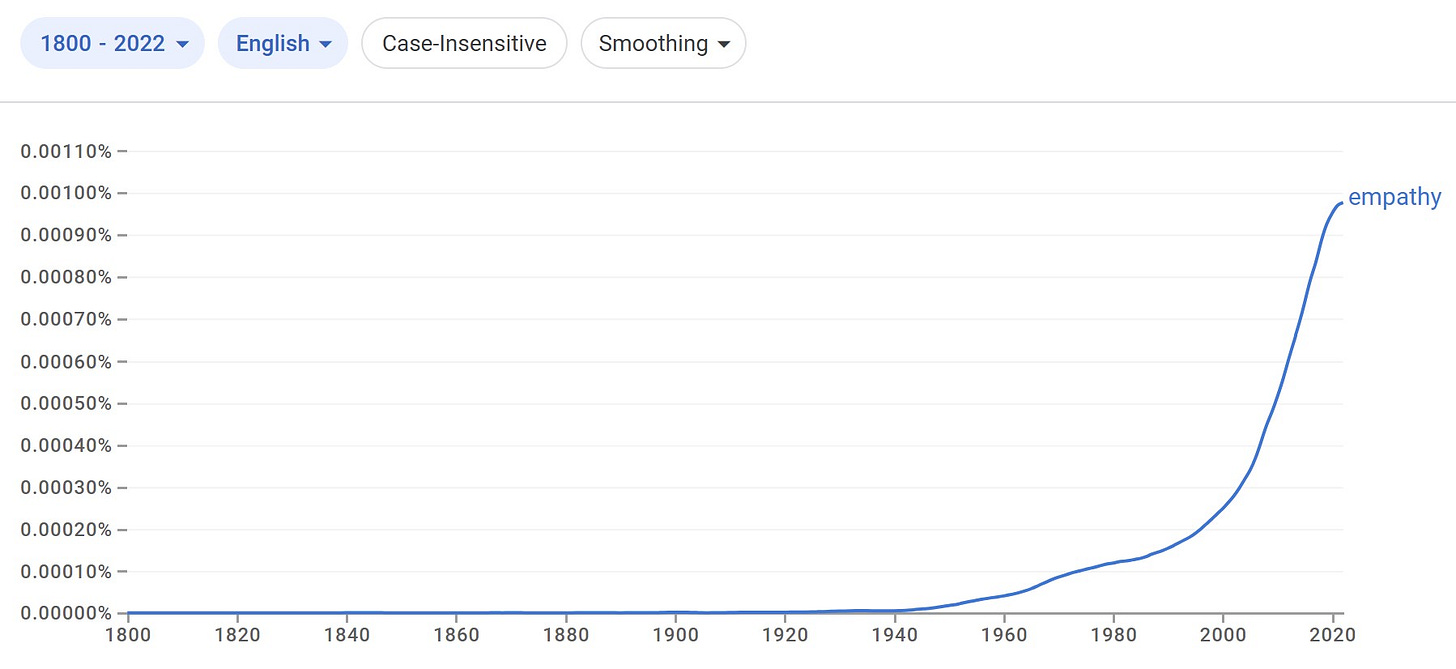

The social sciences shape mainstream culture because they define which human behaviors are normal and healthy and which are aberrations to be cured. In a patriarchal country like Iran, for instance, female immodesty is often considered a mental illness, and a mental health clinic will soon open to “treat” women who refuse to wear the hijab. Meanwhile, the West’s matriarchal field of psychology has arguably biased society in the other direction, such as by normalizing empathy, and defining a lack of it as a problem to be fixed. This would help explain why the last two decades have seen a surge in the use of the word “empathy” in published books.

A consequence of Western society’s idolization of empathy is that certain myths have been allowed to spread because they’re empathogenic: they foster empathy. The most important of these myths is “blank-slatism”, a model of people as “blank slates” who have little to no inherent nature, but are shaped largely by culture. Under this view, people only become criminals due to negative experiences such as abuse or poverty, so a core part of any criminal case becomes identifying the trauma that produced the criminal. This is a seductive view for social scientists because it means anyone can be “fixed” through exposure to the right environment. Further, this view encourages empathy because it’s easier and more rational to empathize with others if we’re all fundamentally the same person, differentiated only by experience.

The trouble is, we’re not. Blank-slatism has been resoundingly disproven by decades of twin studies. It’s also disproven by common sense; if people become criminals only because of experiences like abuse or poverty, then everyone who was poor or abused would become a criminal, yet the overwhelming majority don’t (and many who are neither poor nor abused do). In fact, the majority of crime is committed by a small minority of repeat offenders, suggesting personality plays a key role.

Since we have intrinsic natures, our minds are more alien to each other than we might assume. This makes empathy an inaccurate way to understand the behavior of others. A recent study found that, while women do tend to be more empathetic than men, they’re no better at inferring other people’s mental states.

The main use of empathy is to help people form personal connections with others. It’s a social guide, not a moral or judicial guide. And yet people are being encouraged to use empathy as a moral guide, and in this capacity it becomes dangerously delusional.

A chief reason empathy misleads us is that we never empathize with people, only with the people we think they are. We take the bare bones of what we know about them, and flesh the rest out with assumptions. Sometimes we fallaciously use ourselves as the model for them, presuming our own feelings and motivations are theirs. More dangerously still, we begin to idealize them.

Empathy is an act of opening ourselves up to the feelings of others, and in doing so, we become vulnerable to feelings that can cloud our judgment. If we identify too strongly with someone, our emotional connection to them can cause us to behave like their lawyers, engaging in mental gymnastics to defend our idealized image of them. Instead of judging their innocence by their actions, we judge their actions by their assumed innocence, looking for the most sympathetic explanation for everything they do.

For instance, Lyle and Erik supporters sometimes argue the brothers’ lavish spending spree with their freshly murdered parents’ money was not a sign of greed but just more evidence they were traumatized, because it showed they were trying to cope through “retail therapy”. As if the natural response to a lifetime of sexual abuse is to purchase a buffalo wings restaurant.

Empathy produces fiction in the mind because it’s ultimately a form of imagination. The fact that movies and literature can make us empathize with fictional characters shows how easily our empathy can be hacked. This may explain why Cooper Koch, who plays Erik Menendez in the hit Netflix show Monsters, became convinced the brothers are telling the truth, and even visited them in prison. He had to put himself in Erik’s shoes as a fulltime job, but he never actually empathized with Erik; only with the idealized version of Erik he’d chosen to portray.

Despite deluding so many people, empathy rarely gets any pushback in the West today, because there’s an assumption that it is the key to compassion, and opposing compassion is a good way to get ostracized from polite society. However, not only is empathy not required to be compassionate, it can actually be an obstacle to it. In his 2016 book, Against Empathy, the psychologist Paul Bloom compares empathy to a spotlight; we only shine it on a few handpicked people at a time, and whenever we do, we lose sight of, and concern for, everyone else.

But empathy doesn’t just make us unconcerned for others, it can also make us actively spiteful toward them if we feel they’ve troubled the object of our empathy. In one study, participants were told of a contest between two students for a small cash prize. Half the participants read an essay in which a contestant expressed distress at being low on money, and the other half read an essay where she mentioned she was low on money but didn’t express distress. The participants were then told that, as part of a study into pain and performance, they must choose how much hot sauce the contestant’s rival would have to consume. The participants who read of the contestant’s distress demanded the contestant’s rival consume more hot sauce. Empathy for the contestant’s distress drove cruelty toward the contestant’s rival. Furthermore, this empathy-driven spite was strongest for participants who had specific genes that made them more sensitive to vasopressin and oxytocin, hormones that play a key role in empathy.

Empathy-driven spite can also be commonly seen in the real world, such as in the recent case of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson, whose murder was widely celebrated on social media due to his company’s apparent history of denying health insurance claims. In such cases those who empathize with one side’s pain often wish to inflict even greater pain on the other. One might even say empathy is a major cause of sadism in the world.

It should come as no surprise, then, that most of the mock trial studies that find female jurors are more empathetic toward the alleged abuse victim also find they’re more punitive toward the alleged abuser, demanding significantly harsher sentences.

We see this same empathic spite in the online Menendez discourse, most notably in the fact that many people who believe Lyle and Erik are victims also claim they did the right thing by shooting their parents dead, even though the brothers weren’t in imminent danger. Some TikTok clips even celebrate the shooting. Predictably, TikTok is now also filled with clips attacking Pamela Bozanich, the prosecutor in the Menendez brothers’ first trial. One clip, which so far has more than 125,000 likes, shows photographs of Bozanich as a young woman and then as an older one, and states: “This is how you age when you’re a cunt.”

But empathy doesn’t just make people spiteful, it also makes them unjust. In one study, participants watched an interview with a fictitious terminally ill girl called Sheri, and were then asked whether they would move Sheri up the waiting list to receive end-of-life care. The participants were reminded this would disadvantage other terminally ill kids who needed the care more. Of those who’d watched Sheri’s interview but been told to decide objectively, one-third opted to move her up. But of those who’d specifically been asked to empathize with Sheri, three-quarters opted to move her up. Crucially, the participants admitted their decision to favor Sheri was unfair. Their empathy overruled their principles.

This has also been apparent in the Menendez case. Not only did some of Lyle’s friends, like his ex-girlfriend Traci Baker, agree to lie for him in court, but, recently, web users are now knowingly lying on their behalf. A Wikipedia editor called “Limitlessyou” recently added false claims to the “Lyle and Erik Menendez” wiki page to portray the brothers as victims and their prosecutors as villains. One such claim was that Erik's prosecutor, Lester Kuriyama, theorized that Erik's alleged homosexuality suggested José's alleged molestation was consensual. The LA Times article that Limitlessyou cited for this claim included no such quote, because the quote was a fabrication; in reality, Kuriyama had theorized that Erik’s supposed homosexuality may have been the real cause of friction between Erik and José.

The case of Limitlessyou and other Menendez propagandists suggests belief in Lyle and Erik’s innocence can spread like a parasite across the web. Empathic people, opening themselves up to the feelings of others, become infected with an emotionally transmitted disease – an image of the brothers as poor victims – that alters the host’s behavior, making them biased or outright dishonest so they create misleading content that spreads the parasite to other empaths.

The ease with which people who empathize with Lyle and Erik can be made to lie for them casts doubt on two pieces of evidence recently submitted to court to exonerate the brothers. The first of these is a recently “discovered” letter, supposedly written by Erik to his cousin Andy Cano a year before the murders, which includes a reference to sexual abuse. The second piece of evidence is an affidavit by Roy Rossello (a former member of Menudo, a boy band once managed by José Menendez) in which Rossello alleges he was raped by José.

This evidence hasn’t yet been authenticated, and yet in October it was cited by George Gascón, at that time the District Attorney for Los Angeles County, to support his push for a resentencing hearing to free the brothers. Gascón has professed his belief the brothers were abused, in opposition to all actual evidence, and against the decision reached by the jury in 1996.

As the county’s most senior prosecutor, Gascón should’ve been more discerning of a criminal case than the average TikToker or Hollywood celeb, and yet he appears to have been no less gullible. Some have pointed out that when Gascón announced his support for the brothers, he was campaigning for re-election, suggesting it may have been an attempt to increase his popularity among TikTok and Instagram users.

But it’s unlikely Gascón chose to support Lyle and Erik only for power; his political history suggests he’s embraced the same idealistic blank-slatism that characterizes our age of empathy: criminals are not born but made, therefore criminals are victims and require understanding, not condemnation.

Consequently, Gascón has spent his career trying to soften California’s approach to crime. In 2011, he replaced Kamala Harris as district attorney of San Francisco, a position he held till 2019. During his two terms, San Francisco prosecutors filed criminal charges in less than half of cases presented by city police, and violent crime, which had been decreasing, increased 15% while property crimes like vehicle break-ins increased almost 50%.

Gascón then became district attorney of the US’s most populous county, LA. He was elected in the wake of the 2020 George Floyd race riots after pledging to end “systemic racism” in the judicial system. Gascón’s approach to crime in LA was even laxer than his approach in SF. Among his sweeping reforms was a policy of not prosecuting a range of theft and drug-related crimes, and not prosecuting teens as adults, meaning even mass-murderers could be released from jail when they turned 25.

Since Gascón’s policies were based on a fictional model of humanity, they led to a surge in almost all types of crime, particularly theft. Within three years of Gascón becoming DA of LA County, shoplifting increased by a staggering 133%. He soon faced a public backlash, including from his own prosecutors, and a few weeks ago he was ousted from office. The push to unseat him was led by victims of crime, who’d been left in the dark when Gascón chose to shine his empathy spotlight on criminals.

The shocking crime surge under Gascón shows what happens when idealistic empathy is not just confined to TikTok, but becomes legislation: the world becomes more dangerous.

Despite Gascón being evicted from office, the Menendez brothers could still be freed next month, due to a habeas corpus petition they filed last year, backed by huge public pressure. For those of us who value objectivity, the best we can do is to learn, and share, the lesson of the Menendez fiasco: that empathy doesn’t work as a moral or judicial guide. Far from making us good, it makes us gullible, biased, dishonest, cruel, and unjust. If we wish to know who’s right and wrong, guilty and innocent, we should spend less time trying to inhabit other people’s heads, and make more use of our own.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Christina Buttons for her help researching the Menendez case, and to Olivia Ward-Jackson for her help proofreading and editing my ramble down to a readable length.

For those interested in my interactions with Luigi Mangione, I will publish something soon.

Thank you for a thoughtful and insightful article.

Empathy is a basic and useful emotion when genuine , however it has been hijacked by some “special interest(professional victim) groups, because as you point out, it is very easy for emotionally toxic and cynical people to exploit, and essentially gain power over many people, who while genuine in their empathy, are not very discriminating and these two elements have to be balanced to be effective.

Unfortunately many empathic people do not recognise the transactional nature of their empathy. To wit : the people who receive their empathy get attention they would not otherwise get and feel justified, important, etc and the people exercising their empathy get a feeling of moral satisfaction (irrespective of whether their empathy is justified in a given case or even genuine).

In the west currently, sadly such “empathy” has become the norm. In reality it is a sort of mental illness infecting both givers and receivers of its maleficent influence and is used by the cynical for their benefit.

Excellent analysis. You are one of the best cultural critics of the moment. I would just add the blank-slatism is simply another version of the progressive idea that there is no human nature.