The Cure to Misinformation is More Misinformation

Why we need fake news to know what's true

A few months ago we casually wandered into a new epoch of history—the AI age—which looks set to transform society just as profoundly as previous technological revolutions: agricultural, industrial, and digital. The dawn of this new era has mainstreamed a host of once-fringe concerns, from the fear that AI will take all our jobs to the horror of a superintelligence awaking to pursue destructive goals.

Arguably the most pressing of such AI-anxieties is the threat posed by synthetic media to reality itself. Lifelike text, image, and video can now be effortlessly confected on smartphones and personal computers, and we’re already seeing the results.

Fake photographs have won photography contests. Voices of loved ones have been cloned to ask for kidnap ransoms. Students are using text generators to cheat out homework. Lonely men have been tricked into buying the nudes of people who don’t exist. Deepfakes of President Zelensky surrendering have been spread by Russia, while deepfakes of President Putin kneeling before President Xi have been spread by Ukraine. China and Venezuela have flooded the web with computer-generated “journalists” to spread pro-regime talking points. And the US military has been caught soliciting proposals for how best to wage AI-disinformation campaigns on an unprecedented scale.

All of this is just the beginning. The text generator ChatGPT is now the fastest-spreading app in history, and apps for generating image and video are not far behind. In this new world increasingly cluttered with masks posing as faces, how will we discern reality from the unreal? Authorities believe the only solution is greater regulation of misinformation, but this will only exacerbate the problem, and in fact our best hope is not less misinformation, but more.

Misinformation and disinformation (which is misinformation purposefully spread to deceive) are not new problems, and in the last decade a sprawling alliance of institutions has grown to combat them. This “counter-misinformation complex” now comprises government agencies, tech giants, think tanks, the liberal media, and fact-checking organizations, all loosely collaborating to identify and eliminate fake news.

The counter-misinformation complex operates on the principle that the common people are too impressionable to be trusted with their own senses, and therefore what they see and hear must be strictly regulated for their own good. In the AI age, this conviction has only gotten stronger.

In February, UNESCO held its first global conference discussing how best to regulate online platforms to safeguard them against synthetic media. This push for more regulation comes after a strengthening of existing regulations; late last year the European Union’s Digital Service Act (DSA) came into effect, compelling large online platforms like Google, Instagram and Twitter to actively remove content deemed to be disinformation, or face heavy fines.

The DSA’s restrictions on speech were met with predictable praise by the “liberal” press; the Guardian called it an “ambitious bid to clean up social media,” while the Washington Post proclaimed that “The US could learn from Europe’s online speech rules.”

For better or worse, the US does appear to be learning; the EU has opened a new “embassy” in Silicon Valley to “promote EU digital policies” and “strengthen cooperation with US counterparts,” and top US state officials are now pushing for new legislation to criminalize the spreading of election misinformation.

This approach—to fight AI-generated disinformation with greater regulation—will prove a far greater danger than the disinformation itself. Not just because it curtails freedom, but also because it will actually make disinformation worse.

The notion that information traffic can be policed is a relic of the 20th century. It worked in the old, centralized world, but in a distributed world like ours, the information-space is too vast and unpredictable to be top-down regulated.

Brandolini’s law states: “the amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than to produce it.” What this means is that, despite the best efforts of moderators, misinformation will always greatly outnumber information. But it also means that misinformation spreads faster and further than information, so by the time moderators have identified a meme as false and are ready to moderate it, it’s already infected countless minds and cemented itself in the public consciousness. Censors beware: online, you cannot police the present; only the past.

Brandolini’s law is not the only rule counting against online censorship; the Anna Karenina principle suggests that, since there are countless ways to be wrong but only a few ways to be right, those correcting misinformation will accidentally produce misinformation far more often than those promoting misinformation will accidentally produce truth. Censors often have no more idea of what is true than those they censor (see: lab leak hypothesis), so they are fundamentally unqualified to dictate what the rest of us are allowed to see.

All of this was a problem before generative AI, but now the advantage that error generation has over error correction is even greater. Some claim that this advantage can be neutralized by AI itself; many in the counter-misinformation complex are experimenting with language models like ClaimHunter that can find patterns in misinformation to help identify it.

The problem with this approach is that AI is also subject to Brandolini’s law: it requires far less work for AI to produce misinformation than to correct it, so the machines trying to identify misinformation will always be outnumbered and outperformed by machines propagating it.

AI is also subject to the Anna Karenina Principle: it’s easier for an anti-misinformation AI to accidentally promote misinformation than for a pro-misinformation AI to accidentally produce truth. Since AI’s are programmed by humans and trained on human data, they inherit many of our biases and delusions (ChatGPT exhibits a strong left-liberal bias because it’s been trained on the predominantly left-liberal sources of the Western cultural mainstream, like Reddit and Wikipedia.)

What this all means is that censorship, with or without the aid of AI, is not an effective countermeasure against AI-generated misinformation, and governments trying to legislate it, tech giants trying to implement it, and establishment media trying to advocate for it, are like beavers building a dam of twigs in the shadow of an inbound tsunami of bullshit.

So if censorship doesn’t work, how should we deal with the tidal wave of manure?

We shouldn’t.

Over the past two decades, the counter-misinformation complex convinced us all that misinformation is dangerous because it leads to conspiracy theories, which lead to real-world harms. Ask someone in government, or at the New York Times, or at the Poynter Institute, why they’re so eager to regulate information, and they’ll invariably mention January 6th or Russian troll farms.

Certainly, the storming of the Capitol was a direct result of Trump’s lies about a stolen election, deceitfully broadcast by outlets like Fox News. However, the obsessive press coverage given to events like the Capitol riot paint a misleading picture of misinformation itself.

Online misinformation has increased exponentially over the past two decades, yet per capita real-world violence hasn’t even increased linearly; it has in fact dramatically decreased. Not only has violence not increased, nor has the supposed intermediary between misinformation and real-world violence: conspiracy theories.

A recent Cambridge study reviewed the data on misinformation and political violence and found a statistically insignificant correlation. The authors concluded there was no evidence that misinformation leads to real-world harms.

But what about Russian election interference? What about Chinese spamouflage? Surely foreign influence operations are manipulating Western minds and causing people to adopt beliefs against their own interests? A recent longitudinal study analyzed the effect of Russian disinformation operations on voter polarization during the 2016 US election and found it had no appreciable impact.

It turns out people are stubborn in their beliefs, online (mis)information doesn’t easily change their minds, and even when it does, they don’t act on it, because, like most people, they have jobs and family to care about.

In short, there is no evidence that misinformation leads to a significant increase in conspiracy theories or real-world harms, and thus, building a sprawling surveillance and censorship apparatus to try to prevent outlier cases like January 6th is so expensive—in time, money, labor, and freedom—that it fails even the most generous cost-benefit analysis.

Put simply, the counter-misinformation complex was founded on misinformation.

But how did so many experts come to believe it? Part of it may be explained by Upton Sinclair’s famous quote: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

But there’s another, deeper explanation. A well-replicated finding in psychology is the “third-person effect.” This is the tendency for people to overestimate the effect of misinformation on others, and particularly on the masses, due to the mistaken belief that they’re unusually impressionable. This subconscious snobbery is common to us all, but it’s easy to see why it would be particularly prevalent among wealthy, Ivy League-educated intellectuals and policymakers.

Nevertheless, the counter-misinformation complex is correct about one thing: misinformation is bad. Not because it creates conspiracy theories that erupt into real-world violence, but because truth is inherently valuable since it allows us to make good predictions, ignore distractions, and avoid being taken advantage of.

But here’s the thing: not only are attempts to regulate misinformation ineffective at increasing truth, but they’re counter-productive, because they’ll actually make it harder for people to discern truth.

The final goal of the counter-misinformation complex can’t be to create a world free of misinformation, since that isn’t possible. It can only be, at best, to create a few tightly regulated online platforms that are free enough of misinformation that they can be trusted by netizens. If conspiracy theories are memetic viruses, then the best the counter-misinformation complex can achieve is to quarantine small portions of the web from them.

And what are the long-term consequences of living in quarantine? Experimenters tried it with mice, who ended up becoming more prone to disease than control groups. The mice’s immune systems, never stress-tested by microbes, failed to develop effective responses to them. The same is true of our psychological immune systems: quarantine someone from lies and they’ll learn to blindly trust everything. A mind unaccustomed to deceit is the easiest to deceive.

This is the establishment’s grand plan for dealing with the tsunami of bullshit: to lull us into navigating the world on autopilot, utterly dependent on others to tell us what’s true. One could hardly imagine a more disastrous way to live in an age of automated illusion.

Fortunately, there is a real solution. Just as quarantining people from a harm can make them more vulnerable to it, so exposing them to that harm can strengthen them against it. This is how vaccines work; by subjecting us to a controlled dose of a pathogen so our bodies can deconstruct it and learn how to beat it.

Several studies have been carried out to determine the possibility of “vaccinating” people against fake news. In a 2019 experiment, researchers devised a game called Bad News in which people tried to propagate a conspiracy theory online. In order to succeed, they had to deconstruct the conspiracy theory to determine what was persuasive about it and how it could be used to exploit emotion. After playing the game, people became more aware of the methods used to push conspiracy theories, and thereby became more resistant to them.

The study had a robust sample size of 15,000, and its results were replicated with another, similar game, Go Viral. The authors of the studies concluded that exposing a group of people to weak conspiracy theories could fortify their psychological immune systems against stronger ones, just like a vaccine. A recent systematic review of all the known methods used to reduce beliefs in conspiracy theories found that this “vaccination” approach was the most effective.

There are shortcomings with the vaccination analogy, though. A vaccine typically requires only a couple of doses before providing long-lasting, near-total immunity. In comparison, the immunity offered by playing the misinformation games was modest and presumably only as enduring as mere memory.

Due to these limits, the best way to inoculate people against misinformation is not to try to “vaccinate” them, but to use a different process of acclimatization, known as hormesis. This form of inoculation entails not a couple of doses but constant exposure, so the body gradually and permanently adapts to that which assails it.

Ancient Indian texts describe the visha kanya, young women raised to be assassins in high society. They would reportedly be raised on a diet of low-dose poisons in order to make them immune, so they could kill their victims with poisoned kisses. A few centuries later, King Mithridates of Pontus was said to have been so paranoid of being poisoned that he had every known poison cultivated in his gardens, from which he developed a cocktail called mithridate that contained low doses of every known poison, which he’d regularly imbibe to make himself invulnerable. It’s said he was so successful that when he tried to commit suicide by poison after his defeat by Pompey, he failed, and had to ask his bodyguard to do the job by sword.

The process of mithridatism, as it has come to be called, may be what is needed to increase our resistance to conspiracy theories: a dietary regimen of low-strength Kool-Aid to gradually confer immunity to higher doses.

But how exactly do we use mithridatism to immunize entire populations from misinformation? It’s not feasible to expect everyone to download the Bad News game and regularly play it. The answer is to turn the entire internet into the Bad News game, so that people can’t browse the web without playing. This isn’t as difficult as it sounds.

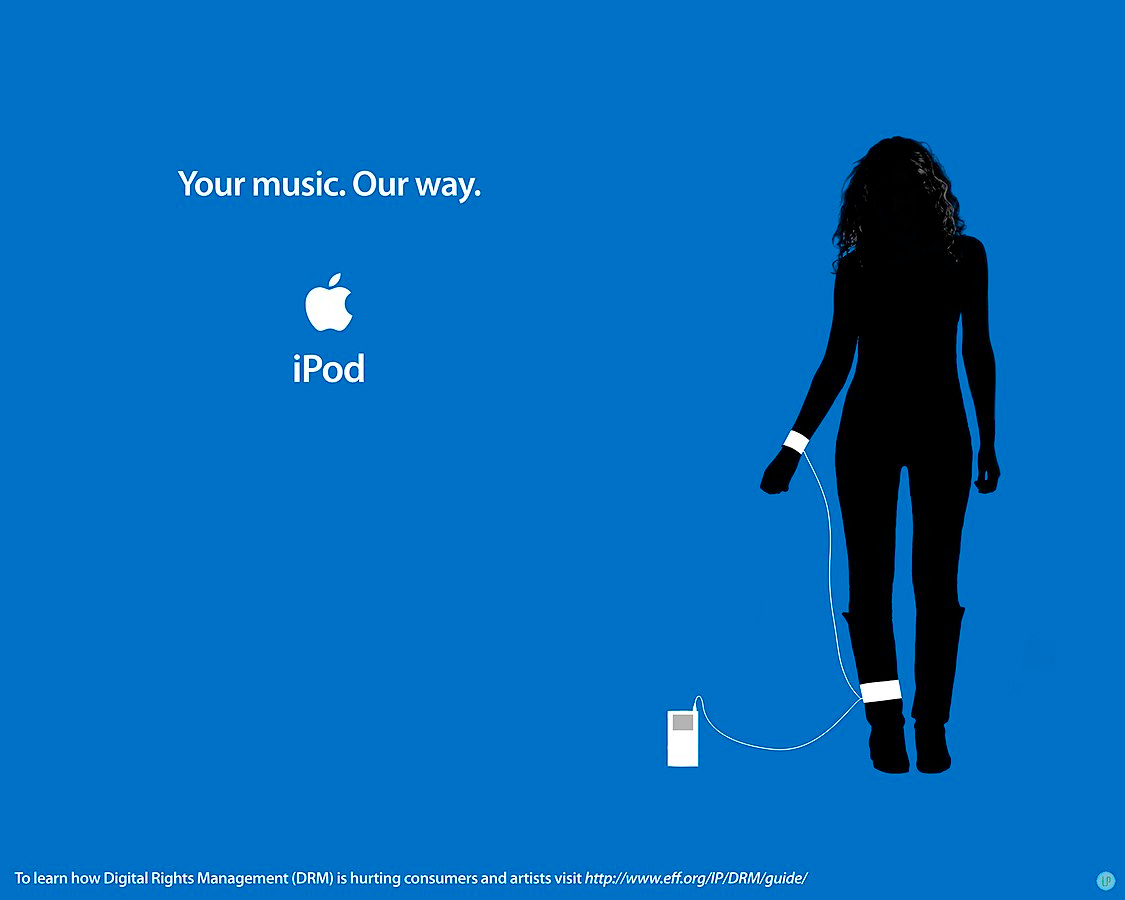

In the 1950s, a group of avant-garde artists known as the Situationists thought the masses had been brainwashed by corporations into mindless consumers. Seeking to rouse them from their sedation, the group employed a tactic called detournement: using the methods of consumerist media against itself. This involved disseminating “subvertisements,” replicas of popular ads that had subtle and ironic differences which made it hard for audiences to distinguish between marketing and parody. The purpose was to foster suspicion and familiarize people with the methods used to manipulate them by making them overt. The idea was that if people were always unsure whether what they were seeing was art or advertisement, sincere or satire, they would become more vigilant.

The tactic of detournement was refined in the 1970s by the writer Robert Anton Wilson, who, with his friends in media, tried to seed into society the idea of “Operation Mindfuck,” a conspiracy theory intended to immunize people against conspiracy theories. It alleged that shadowy agents were orchestrating an elaborate plot to deceive the public for unknown reasons. The details of the plot were irrelevant; all that mattered was that it could be happening anywhere and anytime. Was the ad you just watched genuine, or part of Operation Mindfuck? Was that captivating political speech sincere, or part of Operation Mindfuck? The idea was that if everyone was watchful for the Operation, they would become suspicious of everything they saw, and thereby less vulnerable to all other conspiracy theories.

Neal Stephenson’s sci-fi novel, Fall, or Dodge in Hell, illustrates how this idea could work in the digital age. In the story a woman named Mauve becomes an unwilling celebrity after being doxxed online. Eager to fight accusations against her, she turns to a man named Pluto, who has an unusual plan: instead of trying to silence the accusations, he’ll fill up the web with other accusations, some believable, others ridiculous, to make it impossible to separate truth from lies, and make the public suspicious of all accusations.

This idea has even been used in the real world. Following accusations of Russian meddling in the US election, Putin’s supporters didn’t respond by denying the allegations, but by increasing them. They’d post pictures of, say, a man falling off his bicycle, with a caption reading: “Russians did it!” Eventually, “Russians did it!” became a meme, at which point, accusing the Russians of being behind any plot made you look worse than wrong; it made you look cliched.

The common theme behind all these ideas is that the best way to delegitimize undesirable info is not to censor it, but to propagate other, similar but less believable info. So how could we apply this to delegitimize online misinformation generally?

In the early 1990s, a group of decentralist hackers known as the Cypherpunks considered this very question. According to Stephenson, one of them, Matt Blaze, proposed the idea of a teaching tool he dubbed the “Encyclopedia Disinformatica.” The idea was that the encyclopedia would be the go-to information source, forced on us by algorithms like Wikipedia is now, but it would contain as many lies as facts, so that anyone who trusted it would soon find their trust was misplaced, and thereby learn a valuable lesson about not believing what they read online.

The best part is that creating this encyclopedia, this digital garden of Mithridates, is the easiest thing in the world. All we do is nothing. Synthetic media have already started turning the web into an environment that can teach us not to trust what we’re told. The governments, tech giants, and corporate journalists need only allow the natural ecology of the web to run its course by refraining from trying to police what we can see.

Just as Operation Mindfuck used the form of a conspiracy theory to warn people about conspiracy theories, and subvertisements used the form of ads to warn people about ads, so we can use synthetic media to warn people about synthetic media. We already have deep-fakes that warn of deep-fakes, text generators that sometimes hallucinate so users learn to fact-check them, and viral songs made with cloned voices that inadvertently teach people not to trust voices. The more that people are exposed to deception, the more resistant they become to it, and thus, synthetic media is ultimately a self-correcting problem.

In our new age of infinite misinformation, the counter-misinformation complex’s methods are obsolete, and its goal of a world where people can trust what they see is hopelessly naïve. Its attempts to censor the misinformation pandemic will achieve nothing but briefly quarantine a few online platforms from the inevitable, lulling their users into a false sense of trust, and ultimately making them more vulnerable to deceit.

We should therefore strive to do the opposite—to let misinformation spread so it becomes a clear and constant presence in everyone’s life, a perpetual reminder that we inhabit a dishonest world. Deception is part of nature, from the chameleon’s complexion to the Instagram model’s beauty filters, and it will never be legislated away while life still exists, so let’s stop trying to prevent people from seeing lies, and instead teach people to see through them.

Hmm, there are parts of this idea I like, but it feels incomplete. I agree with the first half (attempts to police misinformation will make the problem worse) and I like the idea of a more “antifragile” population when it comes to information intake, but I’m not sure how this doesn’t ultimately devolve into chaos.

Nobody can keep track of *everything* which is why we do actually need experts in things like medicine, law, science, etc. The true failure of this age isn’t misinformation, but the abandonment of the pursuit of truth by those who should be the most rigorous in pursuing it, in favor of ideology. I feel like that’s the root issue, but I’m not sure how to fix it.

Humans as social beings are naturally wired to trust others. If we have to ingrain people to come out of this natural inclination and not trust anyone/thing by default, we risk significant disruptions in the society.

Also, trust is a significant productivity enhancer. It is much easier to carry out transactions in a high-trust ecosystem, than in a low-trust ecosystem. So we will be imposing significant costs if we take this route of making people ever-skeptical.