The Pathologization Pandemic

Why youth mental illness is surging

“He who—through the wrong diagnosis—

assumes an evil to exist where it does not, plants one in the body.”

— Paracelsus

Across the West, the mental health of young people is deteriorating. More than any previous generation, they express feelings of despair and hopelessness, and they are being diagnosed with mental disorders at an unprecedented rate. An analysis of the data suggests this mental health crisis is a symptom of a malfunctioning society, which is making people sick by teaching them to feel sick.

Deep in the data of the Covid pandemic lie signs of a much stranger pandemic. We know that Covid can lead to a host of long-term complications, collectively known as long Covid, and since men and older people suffer the most complications from Covid, we’d expect that the Covid survivors most likely to report long Covid would be older men. But this is not so.

According to a US Census Bureau survey, women are almost twice as likely as men to report having long Covid, while transgender people are significantly more likely to do so than everyone else. A German study, meanwhile, concluded “there is accumulating evidence that adolescent girls are at particular risk of prolonged symptoms” of long Covid.

Given that Covid tends to affect men more than women, why would long Covid affect women more than men? And given that Covid complications are extremely rare in the young, why would teenage girls be disproportionately affected by long Covid? Finally, why would long Covid affect transgender people most?

The answer lies in the fact that long Covid is not a strictly physical phenomenon. A study of nearly two million people published in Nature found that people who reported three or more symptoms of long Covid included 4.9% of people confirmed to have had Covid and 4% of people with no evidence of having had Covid. So, reports of long Covid are not reliable predictors of a prior Covid infection.

In fact, long Covid correlates about as much with mood disorders as with Covid itself. One study found that people prone to anxiety and depression before Covid infection were 45% more likely to develop long Covid after infection, and the Nature study found that having anxiety and depression before Covid infection almost doubled the chance of reporting long Covid after infection.

This would help explain why women and trans people are disproportionately reporting long Covid: these two demographics have particularly high rates of anxiety and depression.

But why exactly would mood disorders increase the likelihood of reporting long Covid? Some experts have speculated that stress may affect the immune system’s inflammation response to Covid, leading to more serious infections. However, a Turkish study found no correlation between anxiety or depression and inflammation response to Covid.

A much likelier explanation is that, since the symptoms of mood disorders overlap with those of long Covid, people are mistaking distress for the side-effects of viral infection.

The tendency for people to misdiagnose their despair as a medical disorder can be observed far beyond the long Covid phenomenon. Consider the surge in reports of gender dysphoria. Between 2012 and 2022, the number of adolescents referred to the NHS’s Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) for gender dysphoria increased by over 2000%. If the surge were simply due to decreasing stigma around being trans, we’d expect proportionate numbers of both sexes and all ages to come out as trans, but the surge has been driven almost exclusively by young people and natal females.

The group that’s disproportionately reporting gender dysphoria — adolescent girls — is the same demographic as the group deemed in the German study to be disproportionately at risk of long Covid. It’s also the group, besides trans people, deemed most at risk of mood disorders. So, again, it seems many young people, particularly girls, are confusing general distress for another ailment.

And it’s not just reports of gender dysphoria that have multiplied among young people. Increases have occurred for major depressive disorder, attention-deficit disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and various eating disorders. It seems young people and their doctors are increasingly viewing personal issues as medical disorders — we are facing a “pathologization pandemic.”

But why would so many people confuse sadness for sickness? For a start, it’s human nature to look for single causes to complex problems. The physician’s habit of ascribing all of a patient’s symptoms to just one diagnosis led to the formulation of Hickam’s dictum, which states: “A man can have as many diseases as he damn well pleases.” Likewise, it’s tempting to look for a neat and simple reason for people blaming their troubles on a single disorder, but to do so would be to make the same mistake as them. Pathologization can have as many causes as it damn well pleases.

One cause may be cyberchondria, the phenomenon whereby people anxiously google symptoms, and, due to confirmation bias, ignore those that don’t apply to them while focusing on those that do, until they become convinced they have the disorder they’re reading about. Another cause may be social contagion, whereby panic spreads through the power of suggestion. According to a UK study, adolescents who reported parents suffering from long Covid were almost twice as likely to report experiencing long Covid symptoms themselves, regardless of whether they’d actually had Covid.

It’s known that social contagions tend to affect girls more than boys, a disparity that’s likely exacerbated by girls tending to use social media more than boys. But the problem with social contagion as an explanation is that it’s a how, not a why; it offers a means without a motive.

Some have attempted to discern a motive. One is that girls are trying to escape unattainable ideals of femininity. The Instagram arms race of plastic surgery and beauty filters makes natural bodies seem ugly by comparison, and this “selfie dysmorphia” may lead to anxiety and depression, as well as symptoms of gender dysphoria, as pubescent girls become desperate to defy the metamorphosis of their bodies into sexual objects. But this explanation doesn’t shed much light on the rise of conditions like long Covid, autism, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. However, a deeper dive into the data does.

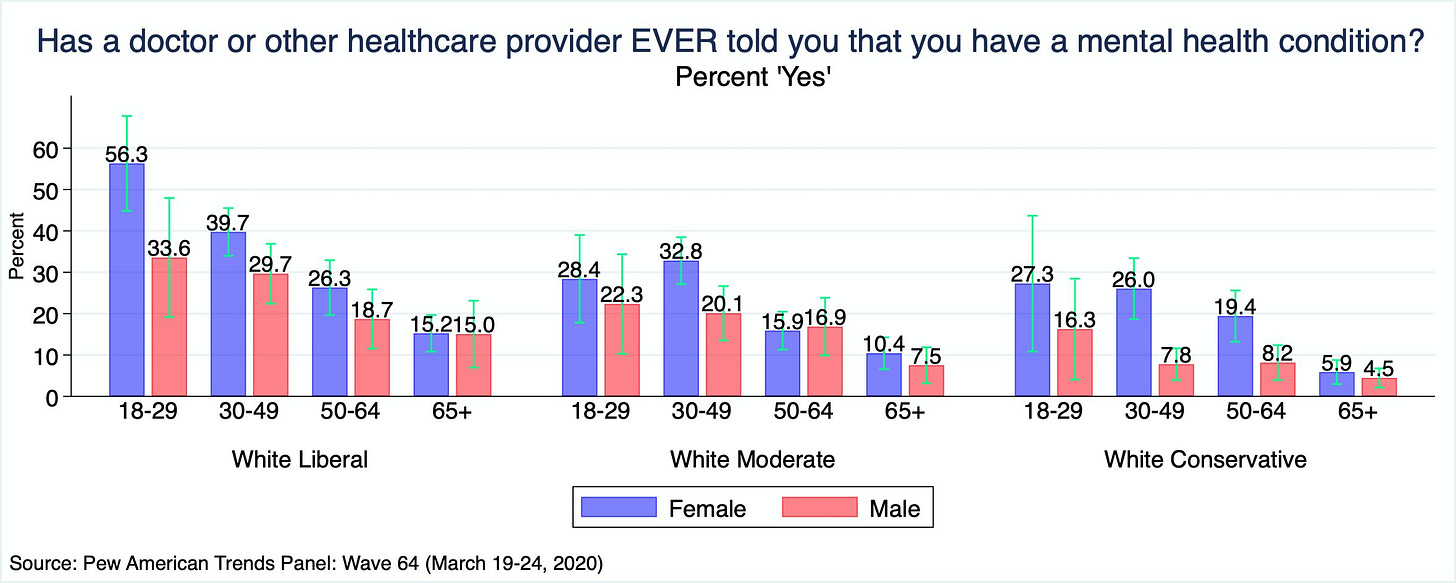

When we include politics in the mental health data, it becomes clear that this isn’t simply about gender. A 2020 Pew survey of over 10,000 Americans found that self-described liberals aged 18-29 were more likely than self-described conservatives of the same age to report suffering psychological problems over the last week. They were also more than twice as likely to say they’d ever been diagnosed with a mental health disorder. Furthermore, those who were “very liberal” were more likely than those who were just “liberal” to report poor mental health. The group most likely to report poor mental health was young white liberal females, an alarming 56% of whom reported having received a mental illness diagnosis.

Crucially, controlling for worldview narrowed the gender gap considerably: liberal men were more likely to report poor mental health than conservative women. It would seem, then, that the mental health epidemic among girls and young women is associated with their tendency to have a more Left-liberal mindset than boys and young men — a difference that’s becoming more pronounced over time.

But why would Leftism be associated with worse mental health? An analysis of data from 86,138 adolescents found, in line with the Pew survey, that between 2005 and 2018 the self-reported mental health of liberals had deteriorated more than conservatives’, and that this deterioration was worst for girls. The researchers blamed this on “alienation within a growing conservative political climate”. However, the New York Times’ Michelle Goldberg debunked this explanation by pointing out that liberals’ mental health woes began while Obama was in power and as the Supreme Court voted to extend gay marriage rights — hardly a conservative political climate.

A more robust explanation lies in the difference in outlook between liberals and conservatives. Central to Leftism is equality, which is best justified by the idea that people’s fortunes and misfortunes are not their own doing, and therefore undeserved. As such, Leftism de-emphasizes the role of human agency in social outcomes, while overemphasizing the role of environmental circumstances. As the West has shifted culturally Leftward — due to most writers and artists leaning Left — the depiction of people as puppets of their environment has become dominant.

Today’s Left-liberal culture teaches young people that their troubles are not their own fault, but the product of various problems beyond their control. These problems may be sociological — late capitalism, systemic racism, the patriarchy — but increasingly they are medical. A common example is “trauma,” a psychiatric term that’s become a knee-jerk justification for everything from street crime to silencing opposing views on campus. It’s a word so overused even clinicians fear it’s lost its meaning.

Most people, however, are happy to have their personal failings blamed on medical issues, because it absolves them of responsibility. It’s not your fault you violently lashed out, you have trauma. It’s not your fault you lack energy, you have long Covid. It’s not your fault you hate the way you look, you have gender dysphoria.

Pathologization is also an effective way to manufacture sympathy. The co-founder of Black Lives Matter, Patrisse Cullors, responded to accusations she’d used donation money to enrich friends and family by claiming that the accusations had given her post-traumatic stress disorder, a diagnosis once reserved for rape survivors and war veterans.

Claims like Cullors’ are instinctively met with sympathy and even awe on the Left, where overeager attempts to destigmatize mental illness have ended up glamorizing it. On social media, young liberals now engage in “sadfishing,” a kind of digital Munchausen’s Syndrome, where people fabricate ailments for pity and clout; some, such as the TikToker “TicsAndRoses,” fake Tourette’s, while others fake multiple personalities. The power of mental health disorders to attract attention online has turned them into fashion accessories, cute quirks to help kids stand out from the crowd, and even boost their dating appeal.

Unfortunately, these designer disorders are not just harmless labels; intentional pathologization by influencers is causing unintentional pathologization among viewers. Reports tell of adolescent girls suddenly developing “TikTok tics” after viewing videos of alleged Tourette’s sufferers. Others tell of adolescents presenting with multiple personalities after watching videos of people claiming to have dissociative identity disorder. As atomization makes people more desperate for sympathy, and competition makes them more desperate for attention, it’s likely that sadfishing and its consequences will only worsen.

But as disturbing as all this is, victimhood culture is not the only force behind the pathologization pandemic. It’s been abetted by a medical industry that has its own incentives for exaggerating the prevalence of mental disorders.

In his 1974 book Medical Nemesis, the Austrian philosopher Ivan Illich described the process of “medicalization,” the tendency for clinicians to recategorize everyday troubles as medical issues. Illich explained that clinicians focus on looking for illness, not health, and this obsessive search, mediated by confirmation bias, leads them to gradually view ever more things as diseased. We saw an example of this in the Tavistock scandal, where the staff of the infamous GIDS clinic, conditioned by ideologues to look for gender dysphoria, became increasingly hasty to diagnose it.

The ability of clinicians to see precisely the symptoms they’re looking for is facilitated by concept creep, the tendency for the definitions of disorders to gradually expand to encompass more people. The rise in autism diagnoses, for instance, can be largely attributed to a diagnostic widening of the autism spectrum. Concept creep is an instance of the Shirky principle, which states: “Institutions will try to preserve the problems to which they are the solution.” The motive is often financial; the number of pregnancies deemed to require caesarean sections has gradually increased because this method of delivering babies is more profitable. Likewise, if you’re simply sad then medical companies can’t monetize you, but if your distress is reclassified as, say, gender dysphoria, those companies can sell you puberty blockers or surgical procedures. By 2021, GIDS accounted for a quarter of the Tavistock trust’s income, and in the U.S. the sex reassignment surgery market was valued at $1.9 billion and is projected to expand at a lucrative compound annual growth rate of 11.23%.

So, we have a medical industry that is both financially and ideologically motivated to overstate the prevalence of illness, and we have a victimhood culture that encourages people to view themselves as oppressed by things they can’t control. In the middle of this we have ordinary people tempted to blame their problems on medical issues for the sake of easy answers.

These three entities together form a mutually reinforcing system. The late philosopher Ian Hacking, in his book Rewriting the Soul, details how in the 20th century, the press, the public, and the medical industry operated in tandem to create new forms of madness out of mere gossip. Prior to 1970, there were almost no cases of multiple personality disorder (now known as dissociative identity disorder), but after one case was well-publicized by the media, many people began using the concept of multiple personalities to make sense of their own problems, conforming — wittingly or otherwise — to the official symptoms of the disorder. When clinicians speculated that people may invent multiple personalities to deal with childhood sexual abuse, people began to invent multiple personalities to deal with childhood sexual abuse. Some even suddenly "remembered" being sexually abused, even though the concept of repressed memories has no basis in fact. Initially, patients reported having two or three personalities. Within a decade, the average number was 17.

Thus, patient reports influenced clinicians’ diagnoses, and clinicians’ diagnoses in turn influenced patient reports. Diagnostic criteria became prescriptive as well as descriptive; they told patients how they were supposed to feel and act. Hacking called this cycle of mutual reinforcement a “looping effect”, and it proved so powerful that it turned a couple of isolated cases into an epidemic. A similar looping effect, facilitated by social media, seems to be driving the rise in reports of mental illness today.

This is a problem because imagined sickness can cause real sickness. This occurs in two ways. The first is direct: in rural India, folklore tells that being bitten by a pregnant dog can make one pregnant with the dog’s puppies, and this urban myth created a new illness called puppy pregnancy syndrome. Victims become so convinced they’re pregnant with puppies that they suffer panic attacks and even manifest symptoms of pregnancy, from persistent nausea to the sensation of puppies crawling in their bellies.

But the second way fake sickness becomes real is far more common and insidious.

Remember how Leftism de-emphasizes human agency in the name of equality? Research shows conservatives tend to have an internal locus of control, which means they believe that their decisions, as opposed to external forces, control their destiny. Liberals, meanwhile, tend to have an external locus, which means they believe their lives are determined by forces beyond their control.

People with an internal locus of control, believing they control their destiny, tend to be happier and have healthier habits, like good diets and frequent exercise, while people with an external locus of control, believing they’re at the mercy of fate, have higher rates of anxiety and depression and are more likely to abuse drugs and neglect their health. When you believe you have no control, you don’t.

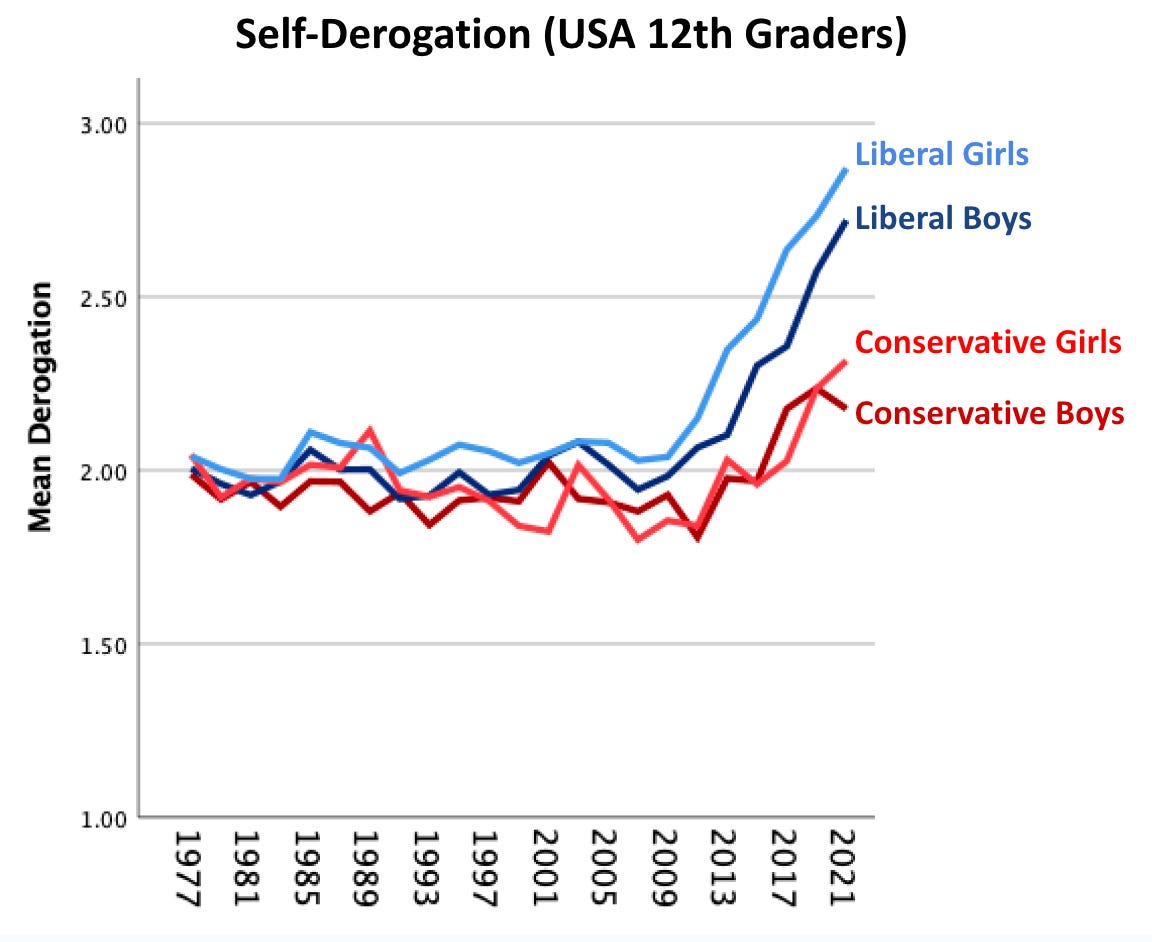

The American psychologists Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge used national survey data of adolescents to map their locus of control. Their findings were based on the proportion of respondents who agreed with statements like “People like me don’t have a chance at a successful life” and “Whenever I try to get ahead, something stops me.” They found that, since the Nineties, the locus of control for all teenagers has steadily become more external, but the shift has been greater for liberals, and greatest for liberal girls.

A common reaction to feelings of disempowerment is self-derogation, the tendency to speak ill of oneself. Haidt and his research assistant Zach Rausch mapped this sentiment using responses to statements such as “I feel my life is not very useful.” The data showed a universal decline in self-worth since 2012, after smartphones and social media became widespread. Again, the decline was stronger for liberals, and strongest for liberal girls.

It would seem, then, that the rapid liberalization and medicalization of young people, enabled by social media, has hindered their self-belief and resilience to setbacks. Many teenagers have subsequently become trapped in a cycle where they feel distress, pathologize it, causing more distress, leading to more pathologization and distress, which eventually becomes textbook anxiety and depression. The rise in diagnoses is therefore not simply an illusion caused by medicalization; society is teaching kids to feel powerless and worthless, which is causing real dysfunctions.

This is the greatest danger of the pathologization pandemic: belief in one’s sickness is self-fulfilling. It’s a disease not of any bodily organ but of hope itself, and it harms its victim by crippling their ability to recover from everything else.

So what’s the solution?

Discouraging kids from left-wing politics would be throwing the baby out with the bathwater (as well as utterly futile). Leftism can be a healthy approach to resolving societal issues, and even a source of hope, if it allows for the possibility of agency and personal responsibility. Likewise, conservatism can become unhealthy if it develops a habit of scapegoating personal issues on globalists, drag queens, or some other bogeyman. The solution to the pathologization pandemic, then, lies not in politics but in psychology.

The polar opposite of pathologization is Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). Although referred to as therapy, it’s closer to a form of mental training. Based on the Ancient Greek philosophy of Stoicism, it teaches a lesson the West has all but forgotten: that our feelings are not always valid, but often deluded and self-destructive. It trains people to overcome harmful emotions by reframing harmful thoughts into alternatives that are more agentic and soluble. So, “That made me angry” becomes “I reacted to that by getting angry.” And “Life sucks” becomes “I feel like life sucks right now.” Where pathologization places problems outside your control, CBT places them within your control. Where pathologization bundles many small issues into one giant insurmountable problem, CBT breaks down giant problems into small manageable pieces.

No approach in psychiatry has been as rigorously tested as CBT, and its effectiveness in restoring agency and reigniting hope is documented by decades of research. Some studies suggest CBT is gradually losing effectiveness, but this is mostly because CBT, like everything else in the social sciences, has been corrupted by amateurization and the desire to be “inclusive” and inoffensive. The newest forms of CBT, such as “Transgender-Affirmative CBT,” are the opposite of traditional CBT because they seek not to transcend feelings but to validate them.

More than ever, a return is needed to the original, Stoicism-based form of CBT, which helped people find strength for over 2000 years, from the philosopher-emperor Marcus Aurelius, who used Stoicism to govern Rome during a time of war and plague, to Vietnam POW James Stockdale, who used it to withstand torture at the notorious “Hanoi Hilton.” If Stoic CBT were taught as part of school curricula, it would help the young overcome the greatest obstacle to their well-being — their own minds.

The ultimate cure to rampant pathologization, then, is to teach the young a time-tested truth, bequeathed to us by history’s survivors: that you are more than the things that happen to you.

Sure, many of the misfortunes that befall you will not be your fault, and you’ll often get knocked down no matter how hard you try to resist. But if you seek explanations for your suffering in things beyond your control, you risk falling prey to a culture and industry that are motivated to keep you feeling ill. So never blame on your circumstances what you can blame on yourself. Look within for the causes and, most times, within you’ll find the cures. Modern society will tell you otherwise, but it’s within your power to defy it, for you are not a helpless leaf in the wind but a mind that holds a world, which, depending on how you think, can be a hell in heaven, or a heaven in hell.

A shorter version of this article appeared in UnHerd. This is the original, full-length version.

"Sure, many of the misfortunes that befall you will not be your fault, and you’ll often get knocked down no matter how hard you try to resist. But if you seek explanations for your suffering in things beyond your control, you risk falling prey to a culture and industry that are motivated to keep you feeling ill. So never blame on your circumstances [for] what you can blame on yourself. Look within for the causes and, most times, within you’ll find the cures. Modern society will tell you otherwise, but it’s within your power to defy it, for you are not a helpless leaf in the wind but a mind that holds a world, which, depending on how you think, can be a hell in heaven, or a heaven in hell."

Fantastic advice! Far too much of the "helplessness" we might experience is learned, or maybe I should say, "taught" by those hoping to gain advantage, either political or economic--and maybe even both--from our internalization of that helpless feeling. Of course, their ability--and only THEIR ability--to help us, is part of the bargain!

As a left-leaning Long Covid sufferer who has used self-motivation and CBT to cope with the condition, I strongly support your conclusions on therapy. However, you spend much of the article going on about 'Leftists' and implying people who (by your own conclusion) need CBT support are imagining their problems. This sets a certain tone that could be used to denigrate those people. You also don't address the possibility that right wing people bottle up their problems or are to proud to ask for help.