What causes delusion?

The prevailing view is that people adopt false beliefs because they’re too stupid or ignorant to grasp the truth. But just as often, the opposite is true: many delusions prey not on dim minds but on bright ones. And this has serious implications for education, society, and you personally.

In 2013 the Yale law professor Dan Kahan conducted experiments testing the effect of intelligence on ideological bias. In one study he scored people on intelligence using the “cognitive reflection test,” a task to measure a person’s reasoning ability. He found that liberals and conservatives scored roughly equally on average, but the highest scoring individuals in both groups were the most likely to display political bias when assessing the truth of various political statements.

In a further study (replicated here), Kahan and a team of researchers found that test subjects who scored highest in numeracy were better able to objectively evaluate statistical data when told it related to a skin rash treatment, but when the same data was presented as relating to a polarizing subject—gun control—those who scored highest on numeracy actually exhibited the greatest bias.

The correlation between intelligence and ideological bias is robust, having been found in many other studies, such as Taber & Lodge (2006), Stanovich et al. (2012), and Joslyn & Haider-Markel (2014). These studies found stronger biases in clever people on both sides of the aisle, and since such biases are mutually contradictory, they can’t be a result of greater understanding. So what is it about intelligent people that makes them so prone to bias? To understand, we must consider what intelligence actually is.

In AI research there’s a concept called the “orthogonality thesis.” This is the idea that an intelligent agent can’t just be intelligent; it must be intelligent at something, because intelligence is nothing more than the effectiveness with which an agent pursues a goal. Rationality is intelligence in pursuit of objective truth, but intelligence can be used to pursue any number of other goals. And since the means by which the goal is selected is distinct from the means by which the goal is pursued, the intelligence with which the agent pursues its goal is no guarantee that the goal itself is intelligent.

As a case in point, human intelligence evolved less as a tool for pursuing objective truth than as a tool for pursuing personal well-being, tribal belonging, social status, and sex, and this often required the adoption of what I call “Fashionably Irrational Beliefs” (FIBs), which the brain has come to excel at.

Since we’re a social species, it is intelligent for us to convince ourselves of irrational beliefs if holding those beliefs increases our status and well-being. Dan Kahan calls this behavior “identity-protective cognition” (IPC).

By engaging in IPC, people bind their intelligence to the service of evolutionary impulses, leveraging their logic and learning not to correct delusions but to justify them. Or as the novelist Saul Bellow put it, “a great deal of intelligence can be invested in ignorance when the need for illusion is deep.”

What this means is that, while unintelligent people are more easily misled by other people, intelligent people are more easily misled by themselves. They’re better at convincing themselves of things they want to believe rather than things that are actually true. This is why intelligent people tend to have stronger ideological biases; being better at reasoning makes them better at rationalizing.

This tendency is troublesome in individuals, but in groups it can prove disastrous, affecting the very structure and trajectory of society.

For centuries, elite academic institutions like Oxford and Harvard have been training their students to win arguments but not to discern truth, and in so doing, they’ve created a class of people highly skilled at motivated reasoning. The master-debaters that emerge from these institutions go on to become tomorrow’s elites—politicians, entertainers, and intellectuals.

Master-debaters are naturally drawn to areas where arguing well is more important than being correct—law, politics, media, and academia—and in these industries of pure theory, sheltered from reality, they use their powerful rhetorical skills to convince each other of FIBs; the more counterintuitive, the better. Naturally, their most virulent arguments soon escape the lab, spreading from individuals to departments to institutions to societies.

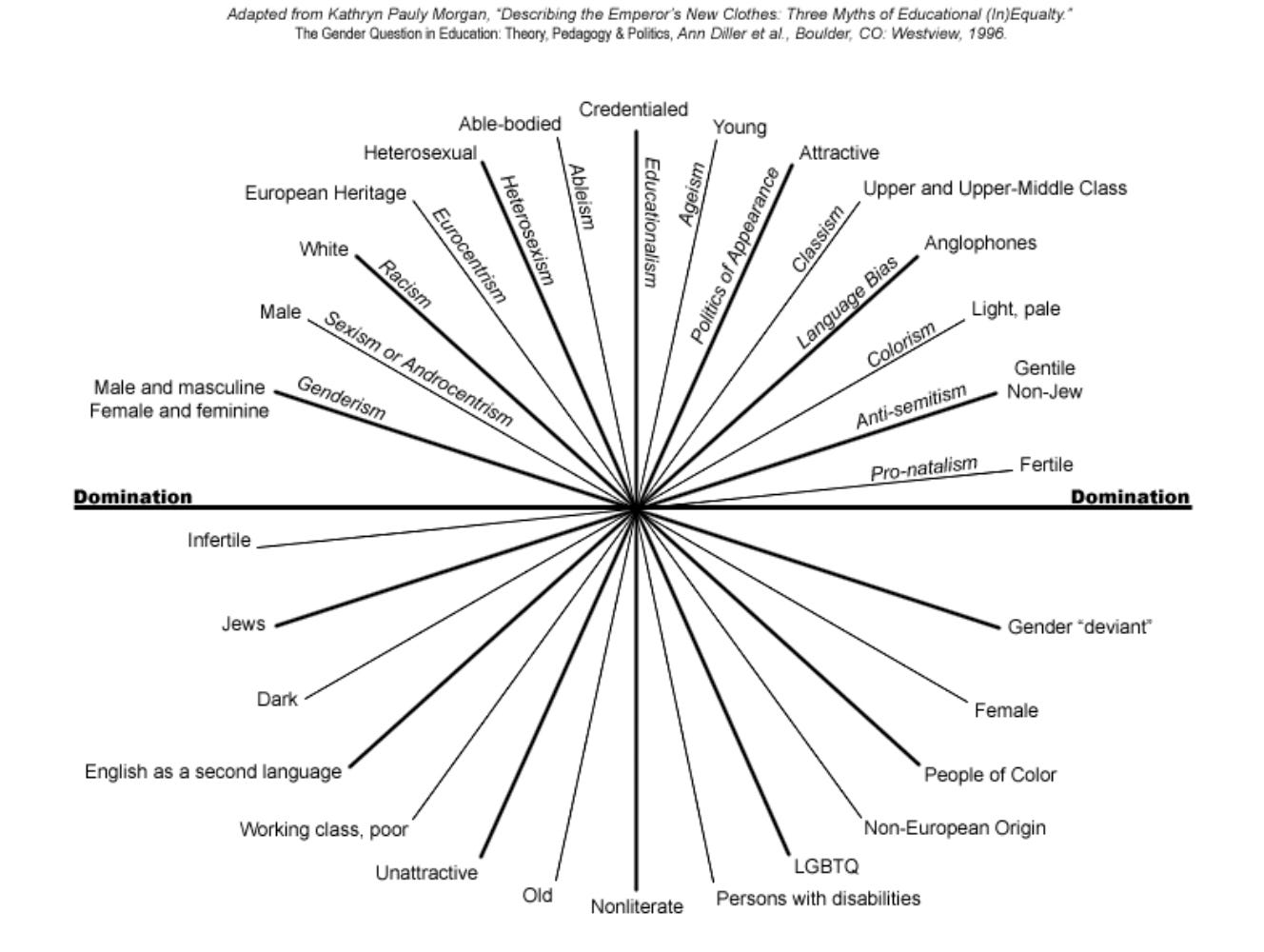

Some of these arguments can now be found everywhere. A prominent example is wokeism, an identitarian ideology combining elements of conspiracy theory and moral panic, which became fashionable in academia toward the end of the 20th century, and finally spread to the mainstream with the advent of smartphones and social media. Wokeism reduces the world down to simplistic oppressor-victim relations, in which people who are white, straight, slim, or male are the oppressors, while those who are nonwhite, LGBT, fat, or female are victims.

Wokeists typically reject claims of objectivity as a weapon created by straight white men to enforce the dominant, “cisheteronormative, patriarchal, white supremacist” worldview. As such, they believe that the purpose of scholarship is not to determine truth but to promote social justice. To this end, they will often use their intelligence to persuade people of arguments that are logically unsound but which are perceived to contribute to a more diverse and equitable world.

For instance, in the late 1960s, some master-debaters decided that fat people are oppressed in a world where slimness is the norm, so they began to carve out a whole field in academia, known as fat studies, to formulate cunning but irrational arguments normalizing obesity. Ignoring decades of medical research showing that being overweight is a serious health risk, fat studies scholars argued that “anti-fat attitudes” are health risks because they could cause obese people anxiety and stress (which may be true), and thus, “fat acceptance” is healthy (which is certainly false). Since then, these activist-academics have developed even more convoluted rationalizations; many now argue that wanting to fight obesity is white supremacy because black women are disproportionately overweight.

Just as fat studies was created to rationalize obesity in the name of “social justice,” so another academic field—gender studies—was created to concoct well-meaning but dishonest arguments for transgenderism and gender nonconformity. One such argument—that sex is a spectrum—is often justified on the basis that there’s no single thing that distinguishes all men from all women. Such an abstract explanation is seductive to an intellectual, but beneath the allure it’s just an example of the univariate fallacy (it’s true that no single thing distinguishes all men from all women, but no single thing distinguishes all cats from all monkeys either; is this proof of a cat-monkey spectrum?)

Even though FIBs like “sex is a spectrum” and “obesity is healthy” are objectively false, woke academics have made them mainstream through a combination of crafty arguments and idea laundering (the practise of couching opinions in academic jargon and placing them in academic journals, to disguise ideology as knowledge.)

These kinds of master-debatery beliefs now prevail among cultural elites, including those who should know better such as biologists, but they are rarer among the common people, who lack the capacity for mental gymnastics required to justify such intricate delusions.

Despite being irrational, wokeism is nevertheless an intelligent worldview. It’s intelligent but not rational because its goal is not objective truth, or even social justice, but social signaling, and in pursuing this goal it’s a powerful strategy. People who engage in woke rituals, such as telling obese people they’re perfect just the way they are, or encouraging kids to question their gender, or calling for the defunding of the police, signal to others that they’re cultured and compassionate toward society’s designated downtrodden. Their demands often end up hurting rather than helping the marginalized, but they make some people feel good for a while, and they increase their own social status, which explains why wokeism is most prevalent in industries where status games and image are most important: politics, media, academia, entertainment, and advertising.

Wokeism is what happens when identity-protective cognition is allowed to run rampant through cultural institutions like Harvard and Hollywood. But while wokeism is currently systemic in the West, in the 1800s the dominant racial ideology in America really was white supremacy. As a result, the master-debaters of that age often used their reasoning to justify anti-black racism. An example would be the American physician Samuel Cartwright. A strong believer in slavery, he used his learning to avoid the clear and simple realization that slaves who tried to escape didn’t want to be slaves, and instead diagnosed them as suffering from a mental disorder he called drapetomania, which could be remedied by “whipping the devil” out of them. Like the fictitious disorder that white people are diagnosed with today—white fragility—drapetomania is an explanation so idiotic only an intellectual could think of it.

Cartwright’s case shows that the problem of runaway rationalization is not just a disorder of today’s woke intellectuals, but of educated people of any persuasion and any time. And that includes you. Since you’re reading about intelligence right now, you’re likely above average in intelligence, which means that you, whatever you believe, should be extra vigilant against your intellect being commandeered by your animal impulses.

But how does one do that, exactly? How does an intelligent person avoid a disorder that preys specifically on intelligence?

The standard rationalist path is to try to avoid delusion by learning about cognitive biases and logical fallacies, but this can be counterproductive. Research suggests that teaching people about misinformation often just causes them to dismiss facts they don’t like as misinformation, while teaching them logic often results in them applying that logic selectively to justify whatever they want to believe.

Such outcomes make sense; if knowledge and reasoning are the tools by which intelligent people fool themselves, then giving them more knowledge and reasoning only makes them better at fooling themselves.

I’ve been tweeting about irrationality since 2017, and in that time I’ve noticed a disturbing pattern. Whenever I post of a cognitive bias or logical fallacy, my replies are soon invaded by leftists claiming it explains rightist beliefs, and by rightists claiming it explains leftist beliefs. In no cases will someone claim it explains their own beliefs. I’m likely guilty of this too; it feels effortless to diagnose others with biases and fallacies, but excruciatingly hard to diagnose oneself. As the famed decision theorist Daniel Kahneman quipped, “I’ve studied cognitive biases my whole life and I’m no better at avoiding them.”

This is not to say that education is futile. Learning can help to limit motivated reasoning—but only if it’s accompanied by a deeper kind of development: that of one’s character.

Motivated reasoning occurs when we place our intelligence and learning into the service of irrational goals. The root of the problem is therefore not our intelligence or learning, but our goals. Most goals of thinking are not to reach objective truth but to justify what we wish to believe. There is only one thing that can motivate us to put our intelligence into the service of objective truth, and that is curiosity. It was curiosity that was found by Kahan’s research to be the strongest countermeasure against bias.

So how do we make ourselves curious?

Good news: if you’re reading this, you’re probably quite curious already. But there’s something you can do to supercharge your curiosity: enter the curiosity zone. Basically, curiosity is the desire to fill gaps in knowledge. As such, curiosity occurs not when you know nothing about something but when you know a bit about it. So learn a little about as much as you can, and this will create “itches” that will spur you to learn even more.

Curiosity is essential to directing your intellect toward objective truth, but it’s not all you need. You must also have humility. This is because the source of our strongest biases is our ego; we often base our self-worth on being intelligent and being right, and this makes us not want to admit when we get things wrong, or to change our mind. And so, in order to protect our chosen identity, we stay wrong.

If you define your self-worth by your ability to reason—if you cling to the identity of a master-debater—then admitting to being wrong will hurt you, and you’ll do all you can to avoid it, which will stop you learning. So instead of defining yourself by your ability to reason, define yourself by your willingness to learn. Then admitting you’re wrong, instead of feeling like an attack, will become an opportunity for growth.

Anyone who’s sure they’re humble is probably not, so I can’t say whether I’ve succeeded in becoming humble. But I can say that I always try to be humble. And, well, there’s little difference between trying to be humble and actually being so.

For me, trying to be humble entails the constant interrogation of my own motives. Could my most cherished belief be a FIB? Why do I really believe what I believe? What other reasons beside reason could I have? My self-questioning makes me agonize over every word I write, but in the long term my hesitancy gives me confidence, for by being careful about what I think I develop trust in my thoughts.

Humility and curiosity, then, are what we most need to find truth. By seeking one we also seek the other: being curious makes us humble, because it shows us how little we know, and in turn, being humble makes us curious, because it helps us acknowledge that we need to learn more.

In the end, rationality is not about intelligence but about character. Without the right personal qualities, more education won’t make you a master of your biases, it’ll only make you a better servant of them. So be open to the possibility that you may be wrong, and always be willing to change your mind—especially if you’re smart. By being humble and curious you may not win many arguments, but it won’t matter, for even losing arguments will become a victory that moves you toward the far grander prize of truth.

Once upon a time, ignorance could be used to excuse stupidity. Then we got the internet and found out that ignorance was never the problem.

Amen! - the expert has the most limited perspective on possibility:

"Never confuse education with intelligence - you can have a PhD and still be an idiot."

...and...

“Science is the belief in the ignorance of experts…The experts who are leading you may be wrong… I think we live in an unscientific age in which almost all the buffeting of communications and television -- words, books, and so on -- are unscientific. As a result, there is a considerable amount of intellectual tyranny in the name of science.”

~ Richard Feynman, Quantum Physicist